In our recent post on democratizing cloud cost data to empower product teams, we laid out the three initial goals of the Costs program:

Cloud expenditures are well-understood and predictable.

Cost information is transparently available to product teams, allowing them to make informed tradeoff decisions.

Costs are minimized without sacrificing engineering velocity.

Our initial efforts built a foundation for engineers to easily access cost data and proactive alerts to draw attention to services experiencing an unexpected rise in costs. These tools have been helpful in gaining a baseline understanding of costs across Fullstory services as well as being alerted to sudden cost changes. But how do we gain insight into cost-saving opportunities that may be hidden within our existing infrastructure?

Earlier this year, the Technical Program Management team worked with a group of engineers at Fullstory where we tried to answer the question, “If we wanted to make Fullstory as inexpensive as possible while still offering the same amount of value to customers, what could we do?” The goal wasn’t to force ourselves to prioritize the projects we identified, but rather to further increase our understanding of how our existing services operate and what opportunities exist to save money, should we decide to prioritize those projects.

Modeling the costs of an engineering project

To start, we asked engineers if they already had existing projects in mind where they expected we could cut costs. Engineers who spend time in a mature codebase tend to have a backlog of projects they would implement to make their services more efficient, given the time.

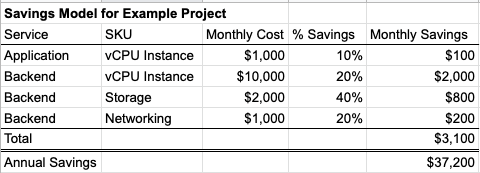

Using this list of engineering projects as a starting point, we would look at our cloud billing line items for the most recent month and make a list of the existing costs that would be affected by each project. We’d then go line by line with engineering and ask, “How much would we save on this specific line item if we implemented this project?” At the end of this exercise, we’d have a number we could use for estimated annual cost savings. Here’s a simple fictionalized example:

In our first pass at the spreadsheet, we would use broad strokes to calculate estimated savings. We’d ask for rough guesses from engineering about how to discount particular line items on the bill. This helped us dial in the order of magnitude of potential savings for each line item so we could better determine how much further effort was needed to validate the cost savings model. For projects that had a relatively small effect on our overall GCP bill, a rough estimate was fine.

For projects with a more significant impact on cloud costs, e.g. where potential savings represented multiple percentage points of the annual bill, we would spend more time validating our cost model. This could involve working with engineering on an additional model from the bottom up (vs top down from the GCP bill), where we laid out assumptions based on how our code works and could then model out potential changes to our implementation that could generate cost savings. Multiple models increased clarity and gave us confidence in the estimated cost savings, which was essential for larger projects.

It’s worth pointing out that for projects with a potentially large payoff, there’s usually significant effort to implement the proposed solution. If these cost-saving opportunities were obvious and easy, they almost certainly would have been implemented already through the normal course of doing business. One of the positive side effects of this process is that projects that require a lot of engineering effort can emerge as “not worth it” when you realize the cost savings will be much lower than originally anticipated.

Compiling projects into a spreadsheet

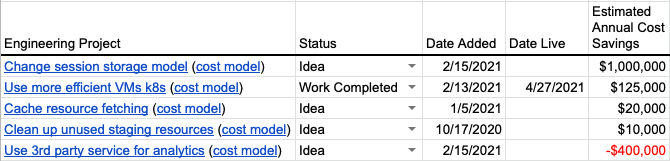

After coming up with an exhaustive list of cost-saving opportunities, we then added all of the potential projects to a spreadsheet:

By listing all of the project ideas in a single spreadsheet, stakeholders were able to get a bird's eye view of all of the potential savings opportunities available. It also helped put things in perspective. Low-effort projects with high savings potential immediately rose to the top, whereas we would deprioritize projects with high effort and low cost savings.

One surprise was that we realized some of the projects would actually cost us money. An idea might have sounded good when we talked about it out loud at an engineering meeting, but when we modeled it out, it ended up being a net loss rather than a gain. Having these items on the spreadsheet gave us a reference point should that project arise in further discussions.

To save or not to save

One of the questions we had to ask was, “How much time and effort should our engineering team spend prioritizing cost-saving efforts?” Every engineering project has an opportunity cost. Given mutually exclusive projects, one that will cut costs and another one that will increase revenue, we have to make a decision about which one to prioritize.

At Fullstory’s current stage, we’re continuing to prioritize growth and scale, which means we tend to focus on the features and services that help us to earn new business and expand the value we deliver to existing customers. Dedicated cost-cutting efforts usually have a negative net present value when factoring in the opportunity costs of research and development intended to grow the business.

Which brings us to an important question: What’s the point of going through the exercise of modeling cost savings projects with engineers if you’re not going to prioritize them?

Further increasing cost awareness

By going through the exercise of modeling cost-saving opportunities, we’re able to have our cake and eat it too. After collaborating with our engineers, we now have a list of shovel-ready projects that we can pick up should we ever need to prioritize cost-saving efforts. Some projects seem immediately obvious while others will sit on the backburner. But even in an environment where growth wins over cost savings, this effort pays dividends.

Individual engineers throughout the organization have become more aware of costs, which is one of the goals of the Costs program at Fullstory. This means that the same engineers who will be deployed on R&D projects for the purpose of increasing revenue will have developed better instincts about how their services contribute to costs.

Perhaps the most important outcome of the Costs program at Fullstory is that costs are minimized without sacrificing engineering velocity. The real outcome of modeling potential cost savings isn’t just a spreadsheet with a list of ways to save money. It’s a deep awareness of costs such that cost-saving efforts become seamlessly integrated into the normal course of engineering work.